Someone recently asked me a fun question: Do hippos count as dragons?

When I was a kid, I mean a real little kid, I had this toy, it was a long white board with five white pegs sticking up off it, and there were shapes with holes in the middle of them—stars, triangles, squares, circles, and hearts—and each shape came in five colors—red green yellow blue purple—and I would sit there for hours sorting them onto the pegs. All the same colors together, or all the same shapes together, or all different colors and shapes in a very particular order. I treated the game like a puzzle I was intended to solve, only of course, there was no way to solve it. One of my earliest memories is of the realization that this was not a thing that would reveal an answer to me, and that was the last day I played with it.

When I was eight years old I learned the word bisexual. I wasn’t bisexual until I learned the word bisexual, but I saw the word and read what it meant, and I thought ‘that means the same thing as this inarticulated cluster of feelings and thoughts that I have,’ and that’s how I became bisexual. I felt the same things before and after learning the word, I was the same person on both sides of that definition, but in learning the name of the category I took it on and it became the thing I would call myself.

I love the recurrent ‘does a hippo count as a dragon’ type debates that crop up on the internet with the regularity of a moral panic in a country with a twenty-four hour news cycle. If you asked me in front of people why I love these debates, I’d say that it’s because they reveal that categories are completely malleable things, arbitrary and meaningless, useful only for guiding people to an aisle of a grocery store. I’d tell you that the question of whether a hippo counts as a dragon is the height of French absurdism, a Nietschean exploration of the fundamental uselessness of meaning, a challenge to pose an orderly question in order to instill a sense of chaos into every conversation about what definitions can do for us.

I’d tell you that but it would only be a little true. The truth is that I like those conversations because I, like many people, am drawn to categories. I am a total mark for structure. I love labels and data and the way a definition can make a word into a code that, when entered into a conversation, can stand in for a concept that would otherwise have no edges to grasp. It feels ridiculous to try to express affection for the fact that words mean things but look: humans simply cannot stop creating new ways to share our feelings and ideas with each other. All we want is to be understood and so we say to each other, over and over again, please understand me, I will try to make it easy for you, just use this word to understand me, please try to understand me as hard as I am trying to be understood.

I am not saying that asking if a hippo counts as a dragon is the same thing as searching for unconditional love and understanding from the people around us. I’m just saying that this is why it’s attractive to ask these questions of each other, these questions about hippos and dragons. We can be like kids in bumper cars, choosing wilful misunderstanding without really hurting each other, taking strong stances that ultimately mean nothing, pretending to come to cosmically important realizations and then returning to lives where nothing is changed. If I say that I think a hippo counts as a dragon, I’m not likely to be denounced by my community, driven off social media by a flood of harassment, driven out of my home by a spouse who can’t reconcile the person I am with the person they decided I was. I won’t lose my job, my home, custody of my children, the right to visit my partner in the hospital when they’re dying. Nothing will be taken away from me. I can cause some debate, possibly a brief controversy, and then I can close my laptop and walk to my kitchen and chop mint for a watermelon salad I want to make, not for lunch or for dinner but just for the moment I desire it, and my hands won’t even shake while I do it.

Please try to understand me as hard as I am trying to understand you, is how it was when I first had to explain to someone what the word ‘nonbinary’ means. Please try to understand me as hard as I am trying to understand you, is how it was when I asked a neurologist to help me figure out what was wrong with my legs. But if I try to explain to you why a hippo is or is not a dragon, it isn’t that way. Neither of us is trying to learn the other one in a way that is confusing and painful and new. We aren’t even really trying to learn about hippos or dragons, although we probably will, in the process of steering our bumper cars toward each other, laughing and then slamming against our seats with the safe impact of what we will pretend is a real argument.

Is a hippo a dragon? Hippos live in the water but don’t breathe water and some dragons do that too. Hippos are violent and some dragons are violent. Hippos are big and scary and don’t let Fiona the baby hippo make you think otherwise, that zoo is putting Fiona in front of you to rehabilitate their image after the thing with the gorilla and fine, it’s working, but don’t let her make you forget that hippos are very scary animals. Dragons are pretty scary too, and if a zoo had a baby one and showed me pictures of it I’d probably forget the other stuff that happened at that zoo, and I’d probably forget that dragons are scary until someone reminded me.

So maybe hippos are dragons.

But this argument only works in an affirming direction, because elimination falls to pieces right away. You might say but dragons are reptiles, and I would say sure some dragons are reptiles but some dragons have hairy beards and wouldn’t that make them mammals? You might say what about wings, but then lots of dragons from lots of traditions around the globe don’t have wings at all. You might say that dragons lay eggs, but I’m pretty sure people just decided that because we know that most snakes lay eggs, and then again anacondas and rattlesnakes and boa constrictors all give birth to live young, so when you get down to it we can’t really know if that one is a hard and fast rule.

So if you ask me if a hippo is a dragon, I’ll probably say I don’t know, are you a veterinarian that specializes in exotics and needs to perform a risky kidney transplant or are you a scuba diver wondering how safe the water is or are you just some guy on the internet who wants to climb into bumper cars and have a fun little pretend-debate? That’s what I’ll probably say, if you ask me that question.

But if you ask me whether a hippo is dragon enough to count, I’ll say yes. Because that’s the question that comes into the conversation when we get out of our bumper cars and onto the road, when we take our definitions and our categories and we stop applying them to hot dogs and raviolis and dragons, and we start applying them to each other. Whenever this question comes up as a hypothetical—the question of who counts as what things—all kinds of arguments leap into the conversation, reasons to say no, no, we have to build the walls thicker and higher, we have to be strict, we have to be selective. There are bad people in this world, these arguments insist, and they’ll use permission to claim an identity as a weapon and we mustn’t let it happen, we mustn’t let them in.

But when the hypothetical dies a weary death and the question comes up in real life, things are different. And it does come up all the time, that question, am I enough to count as part of this group. People ask me this about gender and they ask me this about sexuality and they ask me this about disability. It happens often enough that when a friend carefully ventures can I ask you about? I start warming up a yes, you’re enough because I know it will be needed soon.

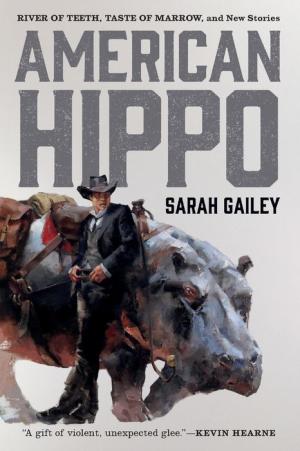

Buy the Book

American Hippo

And the bad people who want an excuse to do harm, they do it whether they get permission or not. In every moral panic about how Things Are Changing and The Balance of Power is Shifting and What About Moral Virtues, the bad people find a way to do bad things. And the bad things they do don’t really lessen the rush of oxygen and the beautiful simple freedom of someone finding a word that will give them a way to say try to understand me. Let me help you understand me.

So, sure. Hippos can be dragons. According to Michael Malone, the author of The Guardian of All Things, dragons appear in virtually every culture around the world, just like queers and disabled people and mentally ill people and people who want so badly to be able to explain their secret tender hearts to those around them. Just like these people who are all around you and always have been, dragons come in so many different forms that it’s almost strange to have a category called ‘dragon.’ Lulu Miller explained this better than I ever can in her perfect book Why Fish Don’t Exist because fish are like dragons are like us in that the category is just a container for something that can’t quite be contained.

I stopped calling myself bisexual a little while ago. I don’t get upset if other people call me bisexual any more than I would get upset if someone told me that a hippo is a dragon, because sure. But I stopped calling myself that when I realized that the person who I am isn’t actually a puzzle that can be solved. I can sort myself into categories over and over again, and none of them will actually answer the question of who I am and why I am and what I am doing in the world. I started calling myself queer because at least that’s a bigger container. It feels a bit like telling a trout that it is a kind of fish or telling a hippo that it is a category of dragon. The trout doesn’t change and the hippo doesn’t change but there’s more space for them to be what they are without having to fit into the rigid constraints of a smaller definition.

Anyway recently someone asked me “do hippos count as dragons?” It was a fun question and I had fun answering it.

Hugo award winner Sarah Gailey lives and works in California. Their nonfiction has been published by Mashable and the Boston Globe, and their fiction has been published internationally. Their novel, Magic for Liars, was an LA Times bestseller. You can find links to their work at their website. They tweet @gaileyfrey.

Anyone else read this and go “oh shit, it’s a metaphor” and struggle to understand anything because their brain was gearing up for a completely different taxonomical question? I feel that conflict between how we categorize identity and how we sort real animals into mythical categories is relevant but I can’t be sure. As I said, I was expecting an article on whether or not hippos are dragons.

I would argue they aren’t based on Lady Trent’s research into dragons but I’m not sure if appealing to the authority of an expert from a secondary world fantasy is legitimate. I mean, she isn’t talking about dragons in our world.

Maybe a dog purrs and cries “meow!” when we’re not looking, but it seems unlikely. (-;

On a more serious note, let’s face it, dragons WISH they were as lethal as the proud, unyielding and frequently aggressive hippopotamus – a creature with the girth, misguided fan following and pronounced tendency to kill people without warning to be observed in His Late Majesty King Henry VIII of England, France & Ireland.

I find it mildly amusing that this appears on the same day as Judith Tarr’s “A Horse by Any Other Name: Anne McCaffrey’s Dragons”, which is about whether the dragons of Pern count as horses (albeit in a more concretely metaphorical way).

The only relevant thought that occurs to me is a stanza from T.S. Eliot’s “The Hippopotamus”:

So: wingéd hippopotamus.

Long ago I read about the origin of the gargoyle.

I don’t remember the source. I don’t vouch for the story. I do enjoy it.

In the darkest of ages, some harbor town in Brittany was cursed with a water dragon. The dragon was called Gargoyle. I don’t know if the name was personal, or name of that class of dragons.

The Gargoyle didn’t spout fire. It spouted water, and created floods.

The town was in a bad way until some Christian hero-saint killed it.

It is in memory of this beast that the architectural, water spouting gargoyles were named.

I participated in a debate on this blog once about whether Godzilla is a dragon. I suggested he’d be classified as one without hesitation by most people at most times. The response was no, Godzilla is not a dragon. Dragons have 4 legs and 2 wings. I replied that’s a very specific idea of what a dragon is, deriving from Medieval Europe. The concept of dragons is much older and more widespread (in fact, allegedly univsersal). It’s been applied to a wide diversity of monstrous beings, although I believe they’ve all been at least partially reptilian in nature. By that standard, hippos are not dragons. But it’s a question of defining your terms, which I guess is this article’s point.

Perhaps a hippo is a dragon in the same way oysters (mollusks) and shrimp (crustaceans) are shellfish, fellow members of a category, but not a taxon.

My first thought was that Gailey’s American Hippo books put hippos, or at least some hippos, in a couple of fantasy-element niches more commonly occupied by dragons — huge, deady, intelligent, ride-able working companions of certain humans, very deadly and inclined toward human-eating when “feral” and on the loose — which I imagined is why Gailey gets asked this question. I wouldn’t have thought to ask if hippos could actually be considered dragons.

Dragons in some fantasy stories give birth to live young. So do many snake and lizard species, though most (not all) of those snake and lizard species are ovoviviparous instead of viviparious, retaining eggs in the body until after hatching, but not nourishing embryos via placentas.

@@@@@#3: I noticed that, too. It’s especially amusing when you consider that “hippo” comes from the Greek word for horse.

I like the point he got to, about not categorizing everything. I disagree somewhat that who we are is a puzzle that can’t be solved. I believe it can be solved, in that, I know who I am, who I was, and where I’m going and what’s waiting for me there, in accordance with my belief system. Now, take away that belief system, and I wonder if I would have a more fluid definition of who I am, or if I’d find some other way to cement that definition. As it stands my belief system contributes in a large way to how I see the world, as it would for anyone.

Without some grounding, I think it’s too easy to just drift in the wind and succumb to any whim that takes you in a given moment. The old, “if you don’t stand for something you’ll fall for anything,” saying. We learn new things about ourselves, hopefully often, and those can contribute to our definitions of self and sometimes change some of them, and that doesn’t mean that our identities of who we are fundamentally have to change.

That being said, I think this was a good article, if a bit wordy, and like I said, I like that in the end he talks about how labels don’t really help us. Seems like everyone is so eager to label themselves and others lately, and I don’t think that’s a good idea; especially labelling others.

This was a beautiful read, thanks for posting.

It touches on using language and categorisation as a tool for either inclusion or exclusion, which I think is so important in writing.

Taxonomically speaking, hippos (family Hippopotamidae) are in the order Cetartiodactyla and are sister (most closely related) to the whales (family Cetacea). In effect hippos are land whales! So, are they dragons? First question is, are dragons reptiles or mammals? If they are reptiles, then hippos are not dragons, but if dragons are mammals, then there is a chance they are related to hippos.

There are three types of dragons, land, air and water. I reckon that the water dragons are actually highly modified toothed whales, and I could construct a plausible phylogeny which would make dragons sister to hippos. So, if a hippo is essentially a land whale, and a dragon is a modified whale, then yes, hippos are dragons.

BTW I am an evolutionary biologist and I teach systematics, so this is the best question ever asked on Tor.com, thank you!

I don’t really buy this philosophy of language. It’s been around for decades now, and it raises a decent point about a certain ultimate lack of precision in language. But it vastly overstates that point. And after decades of strong academic influence, it has in the end failed to have much impact on how even those same academics use language when they’re not doing a sort of academic performance. It’s available to make certain points but seems to have very little relationship to how people talk or write at any time when they’re not consciously making those points.

You can talk about fluid boundaries all you want, but there is not a person out there who, if I talk to them about hippos, will imagine I’m talking about dragons, or if I talk to them about dragons, will have a mental image of a hippo. For real world use those categories are distinct. Cherry-picking a few attributes is not pointing out the limitations of language, it’s sophistry or, at best, people who, unable to understand HOW people use language effectively, think that must mean it’s impossible to do so, even when they can see it being done constantly. But language does actually pretty much work. If basic stuff like hippos vs. dragons was undecidable in normal usage, what hope would we have that complicated talk like the article above would convey any information at all? And yet the author seems confident we’ll pretty much get what’s being said.

There are SOME categories that are fluid and strange and being worked out, where those edge problems and imprecisions of language loom much larger. Gender/sexual/romantic identities are categories like that, sure.

Those categories do NOT say very much about overall language use. The hippo/dragon analogy is a lousy analogy and tries to extend to all language the properties of some rather special cases, in a way which makes our general understanding of language poorer.

If we’re going to start calling things by the names of things they patently are not, why bother with categories in language at all?

I have prepared this Dragon Alignment Chart, in the way of our people, to attempt to resolve this issue.

9. Alex Boyd

*they

The author, Sarah Gailey, uses the pronoun “they.”

When people started trying to teach computers to understand language they realized that words are fuzzy and not clearly defined. A big mouse is usually smaller than a small elephant. An elephant usually has four legs, but an elephant that has lost a leg is still an elephant (but computers that insist on four legs don’t recognize it as an elephant). Probabilistic similarity to a prototype is one attempt to deal with fuzzy classification (the four-legged elephant is closer to the elephant prototype than the three-legged elephant, but the three-legged elephant is closer to the elephant prototype than the four-legged dog, because number of legs is not the only feature that counts).

@14 Oh, that is gorgeous.

I believe I understand the point of this piece but the converse is that categories have to be exclusive as well as inclusive to be useful and, on a practical level, categories are necessary to casual communication. That works for me because I’m willing to put myself into indisputably negative categories.